The PERSPECTIVE Interview

Four industry experts speak their minds

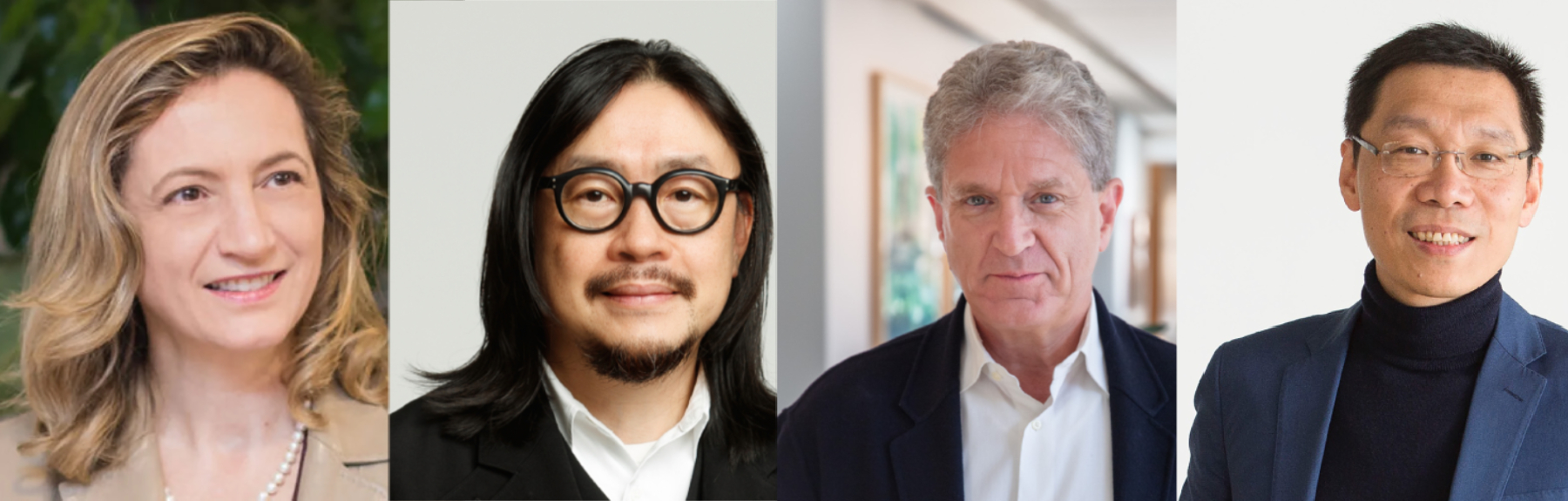

How can architecture and design make a meaningful contribution to climate change, intergenerational housing challenges, cultural preservation, new office models, and other big social issues? We put the following five questions to four leading practitioners (pictured above from left to right) – Dr. Christine Bruckner, of M Moser Associates; Prof. Anderson Lee, of Index Architecture; James Von Klemperer, of KPF; and Dr. Lin Hao, of The Oval Partnership and INTEGER. All four are recognised honourees of the prestigious AIA Hong Kong Honors & Awards, and many of the projects they cite embody the design excellence championed by the program. Here are their frank and insightful answers, which were edited for this article.

Question 1: How can architects move beyond conventional green building ratings to create genuinely climate-resilient design in the face of intensifying typhoons, extreme heat, and other environmental challenges? What innovative strategies are projects using to address these realities?

Anderson:

Green building ratings are nothing but benchmarks for people to hit, and a “pseudo-scientific” way to examine the long-term impact of architecture! The most “sustainable” building of all time to me it is the pantheon in Rome, built in 120 AD! It meets most of the so-called “green building ratings” by sourcing local materials, addressing micro-climate through natural ventilation, and the collection of stormwater through its meticulous drainage system. That it lasted almost 2000 years and almost kept its original function and purpose is its most “sustainable” aspect. I prefer the term “time-resilient architecture” – the longer it can stand the test of time, the more likely that it is a green building!

James:

Our work in climate resilient architecture ranges from rescuing flooded buildings to forward looking situations. In the first case, we took on a project for New York City Housing Authority in Brooklyn, where Superstorm Sandy rendered the entire neighborhood virtually inhabitable. We found ways to build new mechanical plants one story above original grade, to create new outdoor social centers for the population. In the second, we designed a new resilient campus for the HKUST Guangzhou (shown below). We positioned expensive laboratory equipment well above the flood plain by creating an entire site topography which mounds up to the high investment buildings and slopes down to newly configured canals to allow for water retention and runoff.

Lin:

Sustainability is an opportunity to make a better world by aligning global environmental agendas with local action. Our project for 1 Hotel, hailed as the world’s first nature-inspired hotel brand, on Hainan, exemplifies this approach. It serves as a living laboratory—a showcase for climate-resilient design that encourages industry-wide dialogue. In brief, the project transformed an existing resort, with a Balinese design and structure, into one that suits a more sustainable tourism model. We drew inspiration from the rugged beauty of the island, and used local and reclaimed materials wherever possible, while optimising efficient use of natural energy sources. We prioritised concerns such as construction methods, waste management, material sourcing and interior decor choices, all the way to the finer details like the soft-furnishings and accessories in guestrooms.

2. How can architects ensure adaptive reuse projects celebrate authentic local cultural identity while meeting contemporary needs—avoiding both the “hipster makeover” trap and cultural displacement in Asia’s rapidly changing cities?

James:

The key to the future is to work sensitively and extend the fabric of the past… where we marry the appreciation of historically unique workmanship with more contemporary materials and uses. One of our greatest successes started in London, where we doubled the pedestrian and retail vitality of the listed buildings that make up Covent Garden by adding 13 micro projects of bridges and passageways and courtyards that facilitate better use and circulation. This model has been adapted in our work in Shanghai’s Jinling Road district where the long, Shikumen structures have been repurposed for retail residential and hotel use.

Anderson:

Our award-winning church-turned-primary school project in Hang Hau is an illustrative example of how an adaptive reuse project can celebrate local identity and culture. The church served the community in the 1960s when Hang Hau was a small fishing village. The town now houses several hundred thousand residents. The newly built school (shown below) now serves the community by providing alternative educational needs in the area. We’d like to think it is still a “hipster makeover” as the client requested an alternative to the conventional classroom design. We expanded the definition of “traditional” classrooms and emphasized the indoor/outdoor relationship.

Christine:

Adaptive reuse is an effective low-carbon strategy, preserving embodied carbon and reducing construction waste. In rapidly evolving Asian cities, it can also serve as an act of cultural stewardship, protecting authentic local identity while meeting contemporary needs and avoiding displacement. The process benefits from cultural mapping and participatory design, developed in collaboration with community stakeholders. Good examples include the Dyson Global HQ, in Singapore, a former turbine hall reimagined as a high-performance R&D facility, merging contemporary workplace requirements with the building’s historic identity, and Arvato in Shanghai, where we converted light-industrial buildings into creative industry spaces that preserve architectural authenticity while generating economic activity rooted in local culture.

3. How can Hong Kong architects leverage the city’s urban development expertise to lead collaborative projects that address shared technical challenges—such as typhoon-resistant design or urban heat mitigation—across the Greater Bay Area and Southeast Asia?

Anderson:

As we approach the 22nd century, I think architectural practice is becoming more “glocal” …the marriage of global “technical knowledge” with local “indigenous knowledge” I am more interested to find out what Hong Kong architects can “offer” beside our ability to design in densely populated, space-savvy conditions, it seems all too trivial and stereotypical? Do we have any “cultural export” that informs our understanding of local architecture and that is uniquely produced by our own sense of history and identity as a borrowed city in a borrowed time, and now with our newly found affiliation with the Greater Bay Area? I clearly don’t have an answer, and I am still exploring!

Christine:

Hong Kong’s experience in high-performance, high-density urban design positions it as a regional leader in addressing shared challenges such as typhoon-resistant envelopes and urban heat mitigation. Effective collaboration across the Greater Bay Area and Southeast Asia depends on exchanging proven solutions and creating measurable, repeatable results. This approach involves developing regional design toolkits for climate resilience, establishing post-occupancy data sharing agreements, and scaling tested strategies across different climatic conditions. The innovative façade of the BDO Tower in Cebu, which reduced cooling loads by using alternating solid panels and triple-glazed units instead of full glazing, offers learnings for other tropical environments.

4, How can architects create spaces that foster genuine intergenerational connections rather than simply co-locating different age groups? What design strategies have proven effective in building community across generations in Asia’s aging societies?

Christine:

Designing for multiple generations involves more than placing different age groups in the same environment. It requires intentional spatial strategies and programming that encourage meaningful interaction, shared purpose, and mutual learning. Effective methods include creating shared thresholds where paths naturally cross, providing visual connections that promote awareness without intrusion, and offering flexible spaces that adapt to varied activities and sensory needs. A good example is the Li Po Chun United World College in Hong Kong (shown below). We created a “learning street” that connects indoor and outdoor spaces, along with seating nooks, event zones, and flexible activity areas that encourage both structured and spontaneous encounters across age groups.

Lin:

We have a tradition of families caring for their elders, but this is less common than it was, so a deliberate approach to intergenerational design and evidence-based community building is so critical. From 2008 to 2017, I led our team on the design of two earthquake-relief community centres in China …. let me highlight one of them, the Swire Community Centre in Sichuan, after the Ya’an earthquake. It didn’t follow the traditional aid model, which begins with institutional donations after which the local government is fully responsible for design, construction and operation. Instead, it adopted a pioneering ‘crowd-creation’ charity operation model, based on input from locals, industry leaders, designers, welfare organisations, scientific research units, builders and volunteers, and open agenda construction plans. The centre opened in 2017, serving left-behind children, women and elderly people, and providing a public welfare platform.

5. The COVID-19 pandemic transformed our working habits and environments, significantly impacting employee expectations, especially among Generation Z. What does the future hold for the concept of ‘office,’ and what are the implications for office building design?

James:

To keep our minds agile and to make a place where we choose to spend long hours even when we have the option to work from home, the workplace has to offer more. Recognizing the new reality that an office building must be a mixed-use building, our urban plan designs start with the introduction of flexible social spaces, cultural uses, educational facilities, and of course, exercise and recreation. This can be seen in our mixed-use neighborhood built by Kerry Properties in Qianhai (shown below) and in the transformation at Canary Wharf of the former HSBC headquarters into a varied function vertical city. We see this trend as a way to make our cities more delightful and desirable places to work and live.

Christine:

The pandemic reshaped the office from a daily obligation into a destination for connection, collaboration, and brand culture. For Generation Z, flexibility, wellbeing, and authenticity are central expectations, with many preferring hybrid work arrangements and seeking environments that match or exceed the comfort and functionality of home. Future offices will be hybrid-ready, incorporating modular layouts, bookable collaboration areas, and technology that supports equitable participation in mixed-presence meetings. They will prioritise wellbeing with air quality, daylighting, biophilic design, and restorative spaces, while making sustainability visible through renewable energy systems and real time environmental monitoring.

In summary

The themes explored in this interview—climate resilience, cultural preservation, regional expertise, intergenerational design, and workplace evolution—focus on the intersection of architecture and social responsibility. Whether addressing typhoon resistance in the Greater Bay Area, preserving cultural identity in rapidly changing cities, or reimagining office environments for new generations, these four architects exemplify the innovative thinking that has made the AIA Hong Kong Honors & Awards a benchmark for architectural achievement across Asia-Pacific. Their collective wisdom, drawn from decades of practice and recognition for design excellence, underscores architecture’s evolving role in creating more sustainable, equitable, and resilient built environments across the region.